Introducing the Happy Valley Band

Making music through machine ears

By David Kant

About two months ago I released the Happy Valley Band’s first album, ORGANVM PERCEPTVS, a project that I like to explain as “pop music heard by a computer algorithm.” The music is jarring and chaotic, out-of-tune and out-of-time, artifact-laden renditions of classic songs many know and love. For some listeners the music is bliss; others find it absolutely maddening and categorically unlistenable. I’ve received responses such as “this is generally distressing to listen to, thanks” and “conceptually fascinating, but I simply cannot bear to listen to it” as well as “completely amazing.” Here is the opening track:

Madonna’s “Like a Prayer” as heard by a computer algorithm and re-performed by humans. From the Happy Valley Band’s ORGANVM PERCEPTVS.

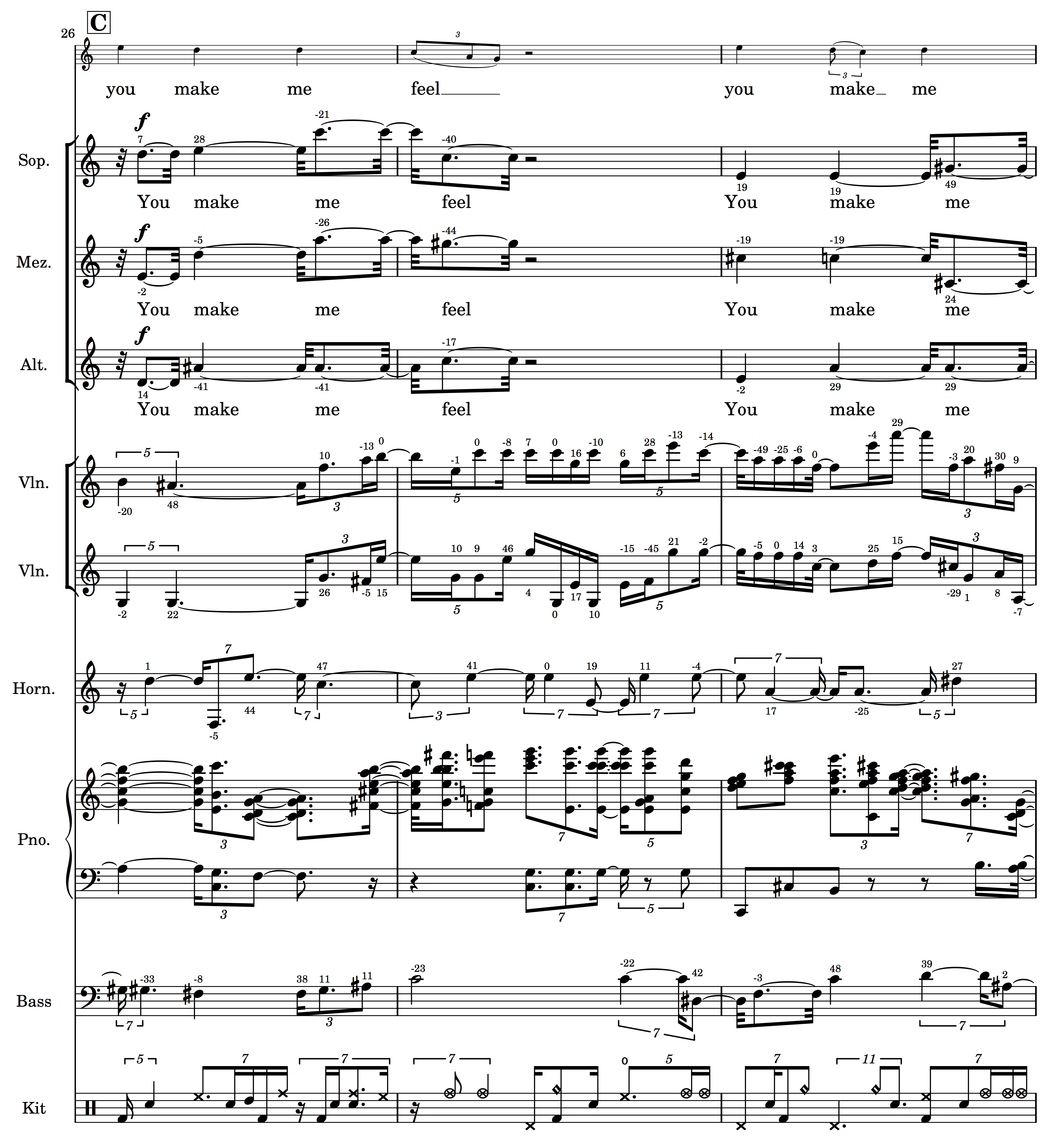

Through the Happy Valley Band I explore the differences between human and machine hearing in the way that I, as a musician, know best: with my ears and my instrument. Starting with original recordings of pop songs, I perform machine listening analysis, render the results in musical notation, and then we, the musicians, play them. My machine listening process first uses source separation algorithms to isolate the individual instruments, then analyzes the separated tracks (source separation artifacts and all) for musical features like pitch, rhythm, dynamics, articulations, and playing techniques, and finally transcribes it all in musical notation for the band to play. The notation is impossibly over-specific, microtonal, and brimming with artifacts of the machine listening process. The liner notes Decomposing Music go into detail about the process of making the music. A typical Happy Valley Band score looks something like this:

Score excerpt of the Happy Valley Band’s (You Make Me Feel Like) A Natural Woman. The small numbers attached to each notehead indicate microtonal tuning deviations in cents.

Score excerpt of the Happy Valley Band’s (You Make Me Feel Like) A Natural Woman. The small numbers attached to each notehead indicate microtonal tuning deviations in cents.

At this point I have spent so much time fitting my brain into these algorithms — listening to their results, tweaking parameters, anticipating new results, then listening back and comparing — that I am pretty sure I have completely rewired the fundamental structure of my hearing mechanism. This project has put me in intimate contact with the idiosyncrasies of machine listening algorithms in way that I never planned for. It is difficult for me to hear these songs any other way, or, really, any other song any other way. This album should probably come with a disclaimer because my bandmembers, housemates, and friends have had the same experience.

What has driven all of this work — the countless hours spent writing custom code and convincing an ensemble of professional musicians to learn thousands of pages of computer generated notation — is a unwavering conviction that we should use machines to hear differently. The Happy Valley Band is about embracing rather than filtering out these differences, and the machine listening process often leads me to hear things in new ways. It turns the opening guitar riff of Led Zeppelin’s “When the Levee Breaks” into a ringing pile of harmonic series just-intoned 7ths and 3rds, or the simple opening timpani roll of James Brown’s “It’s a Man’s Man’s Man’s World” into a not-so-simple sequence of irregular re-articulations with constant foot-pedaling adjustments. Whether you call these differences “artifacts,” “errors,” or simply “too right,” this music is, to my ears at least, no more or less present in the original than an expert listener’s ground truth.

Happy Valley Band’s It’s a Man’s Man’s Man’s World.

When we listen through machine ears, whose ears are they? I’ll be the first to admit that I am not exactly sure what a machine way of hearing would be, or even what a human way of hearing would be. These are open question for me, and I am trying to find an answers through the Happy Valley Band. I do think machine hearing is a moving target; machines hear in as many ways as we design and build them. Machine hearing is a complex of technical, cultural, political, economic, and biological forces. It is something that changes and can be changed.

When I started this project over six years ago, the terms “machine learning” and “artificial intelligence” did not carry the same cultural connotations that they do today. As we now stare directly into a not-too-distant-future in which our entire experience will be mediated, captured, cataloged, and data-fied through the aperture of machine perception organs — be it Google Glass, Facebook’s augmented reality, or whichever tech giant manages to monopolize our daily experience — I believe more strongly then ever in the importance of machine perception systems that expand rather than reify our expectations — or, more realistically, system designers’ guesses at what our expectations may be. I am not content to wait to find out what unexpected results emerge. For me, Humanising Algorithmic Listening means seeking an understanding now and acting on it.

Of all the responses to the Happy Valley Band that I have received, this one gives me hope: “as you listen over time and the pieces somehow hold together and get tighter and tighter, you realize that they kind of aren’t strictly errors, there’s some kind of turbo-charged high level thinking going on.” I like to think of this “turbo-charged high level thinking” as a utopian future in which technology extends rather than enslaves our minds, in which we are cyborgs and we are better off for it.

For notification of future blog posts, follow @algolistening. For HVB news follow @anindexofmusic.

David Kant INTRODUCTIONS

info