HAL Seed Project

A Sense of Being Listened To

By Nicholas Ward & Tom Davis

Over the course of the three HAL workshops there has been discussion around the employment of algorithmic listening within a number of contexts. Some of these have focused on functional, utilitarian uses of algorithms, perhaps for the searching and categorising of databases, and others have been looking at more interpretive definitions of algorithmic listening grounded more generally within creative practice. Throughout these workshops discussions have focused on what listening actually is, be it by human or machine.

Following on from these workshops both Tom and I wanted to tease out what we were referring to as “the sense of being listened to”. I saw this as exemplified in the difference between simple voice control and conversation. In interacting with what are now everyday listening algorithms like SIRI we hear natural language give way to “keywordese”. The human speaker modulates their speaking to make it easy for the algorithim to “understand” what they want: “tea, earl grey, hot”. Then, generally after a pause, some audio response sometimes accompanied with screen based feedback, provides an indication of what was ‘understood’. Though this lurch to keyword speak is often a response to the perceived and sometimes real inability of the system to adequately respond to natural language it is also perhaps simply a shift toward increased efficiency. The system has no feelings. So just hit it up with keywords. No need for good mornings or pleasantries. Anyway, SIRI gives up if you don’t speak to it. It doesn’t care if you are listening to it or not.

This interaction is of course very far from that of conversation between humans: human conversation is characterised by a nuanced, on-going and often unconscious modulation by the speaker of their delivery based on the receivers nods, grunts, gaze, posture, or interruption. The sense of being listened to is central to the activity.

In a musical sense, Di Scipio writes about how listening to a concert can alter a sense of place, even after the music has stopped there is an irrevocable change in the environment. He describes how each new performance provides an ‘experiential audible trace of the meeting of human, machine, and environment’ (2002 p 26)1 or as he puts it later in the article:

Something is welcomed, something is listened to. The one that welcomes is changed a bit after the one that was welcomed has gone. The one that is welcomed is also changed, as it too is one that listens and welcomes.’ (Di Scipio 2002, p.27)

For Di Scipio listening can be thought of as a process that is both reflexive and relational, a process that changes the one that is listened to as well as the one that is listening. We are interested in a similarly reflexive relationship between man and machine. If we can describe our relationships with listening algorithms as social encounters, we can consider them as situations of interaction that change us and the way in which we perceive the world. However, do these interactions also change the algorithmic system? In order for them to be truly relational, the one that is listened to and the one that listens should both be affected by the encounter with the other.

Bringing this in to the context of performance systems, we are interested in thinking about how the system shows it is listening and how that showing changes the human performer’s actions.

Feral Cello Phones Home

In particular Tom has been working on a performance system called the Feral Cello that reconfigures the sound world of an actuated cello live in the performance through a process of machine listening and digital signal processing. Pickups on the cello’s body are fed to a Max patch that analyses the sound for certain pre-recorded sonic gestures. When these gestures are ‘heard’ by the system the Cello switches between different DSP states, effecting the acoustic response of the cello. These gestures are pre-determined by the performer but due to variations in performance and listening errors the system are not 100% predictable. This leads to quite a different performance scenario for the instrumentalist who has to deal with the difficulties of performing with an acoustic system that is constantly being reconfigured live in the moment of performance. Tom would like to extend the listening algorithm in this system such that it has a sense that it is being listened to. In particular he is interested in how can we give our machines a sense of ‘occasion’ that is broader than mere feature extraction.

In performance scenarios, can we develop listening algorithms that are aware of their performance contexts, that respond differently depending on criteria such as the size or the atmosphere of their location, the ‘feel’ of the audience?

Can we give a listening algorithm a sense of being listened to? What would happen if the algorithm were to develop stage fright or performance anxiety?

How does a sense of being ‘listened to’ by algorithms effect the participation of the other performers in this context? How would this affect the human performer who is performing with the system?

These are some of the questions that we would like to explore.

What happens when the listening algorithm’s personality interrupts its ability to pay attention? When the pressures of continuous listening get too much? When anxieties around interaction with strangers give rise to a flight response? Or when the algorithmic agent draws close to the speaker to listen more intently?

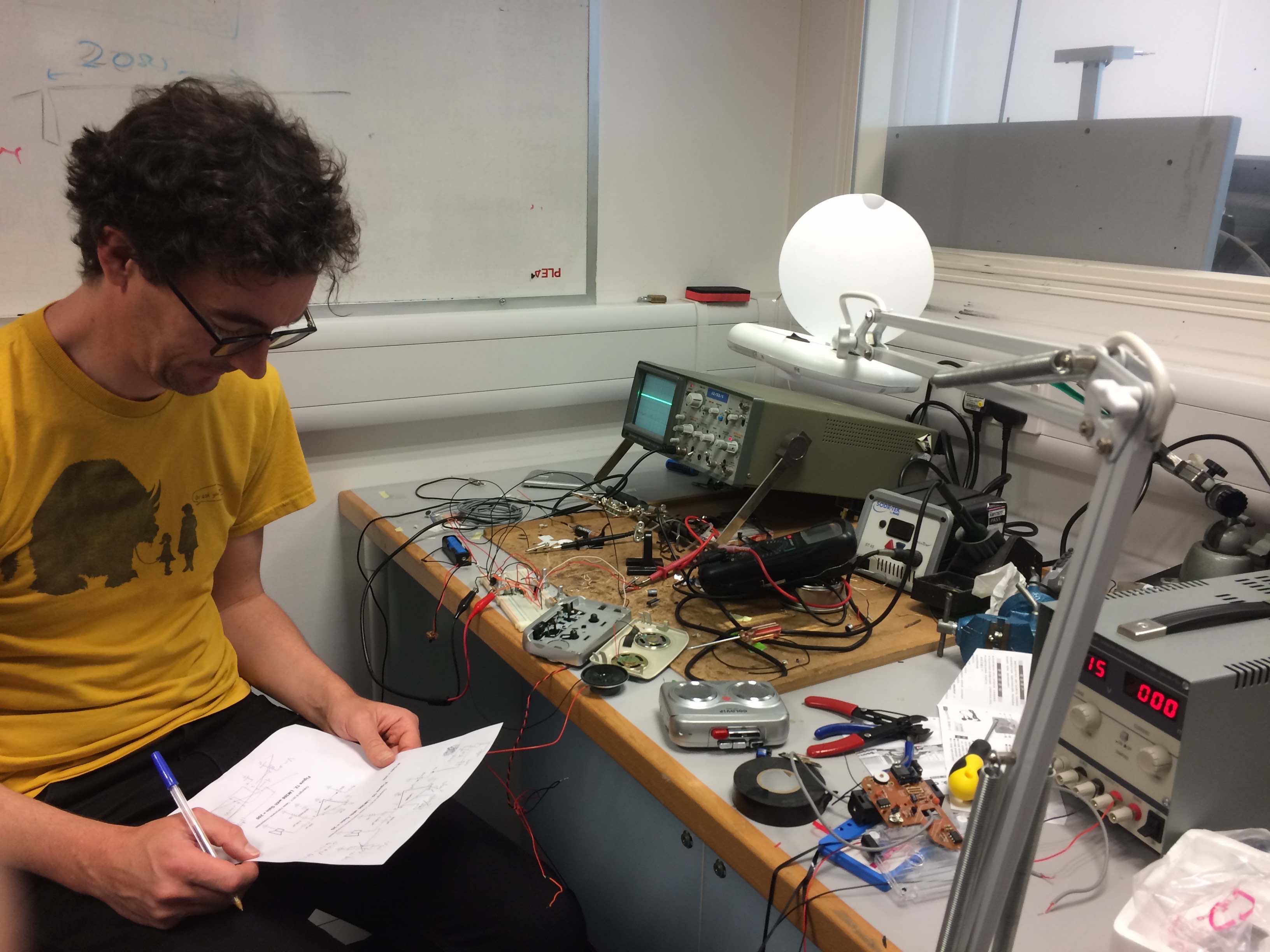

Some initial prototyping:

Over two days in November we sought to move from these questions toward some new work. We decided to eschew the digital entirely, at least temporarily, thereby indulging a contrarian desire to park the actual algorithm. In this age of Deep learning, machine learning, AI and the implied digital computational flavour of all things algorithmic we wanted to begin with an all analogue approach for our listening machine.

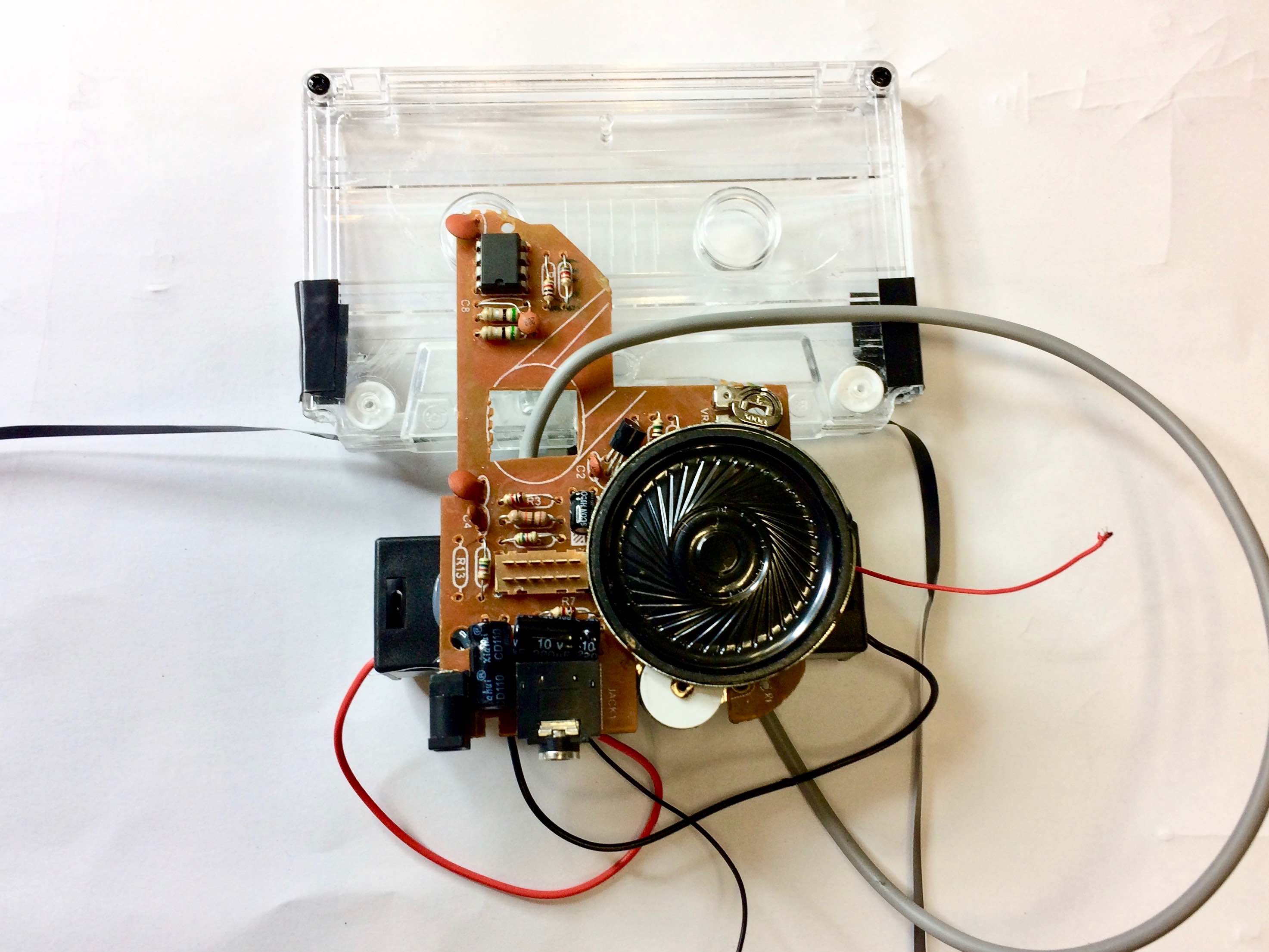

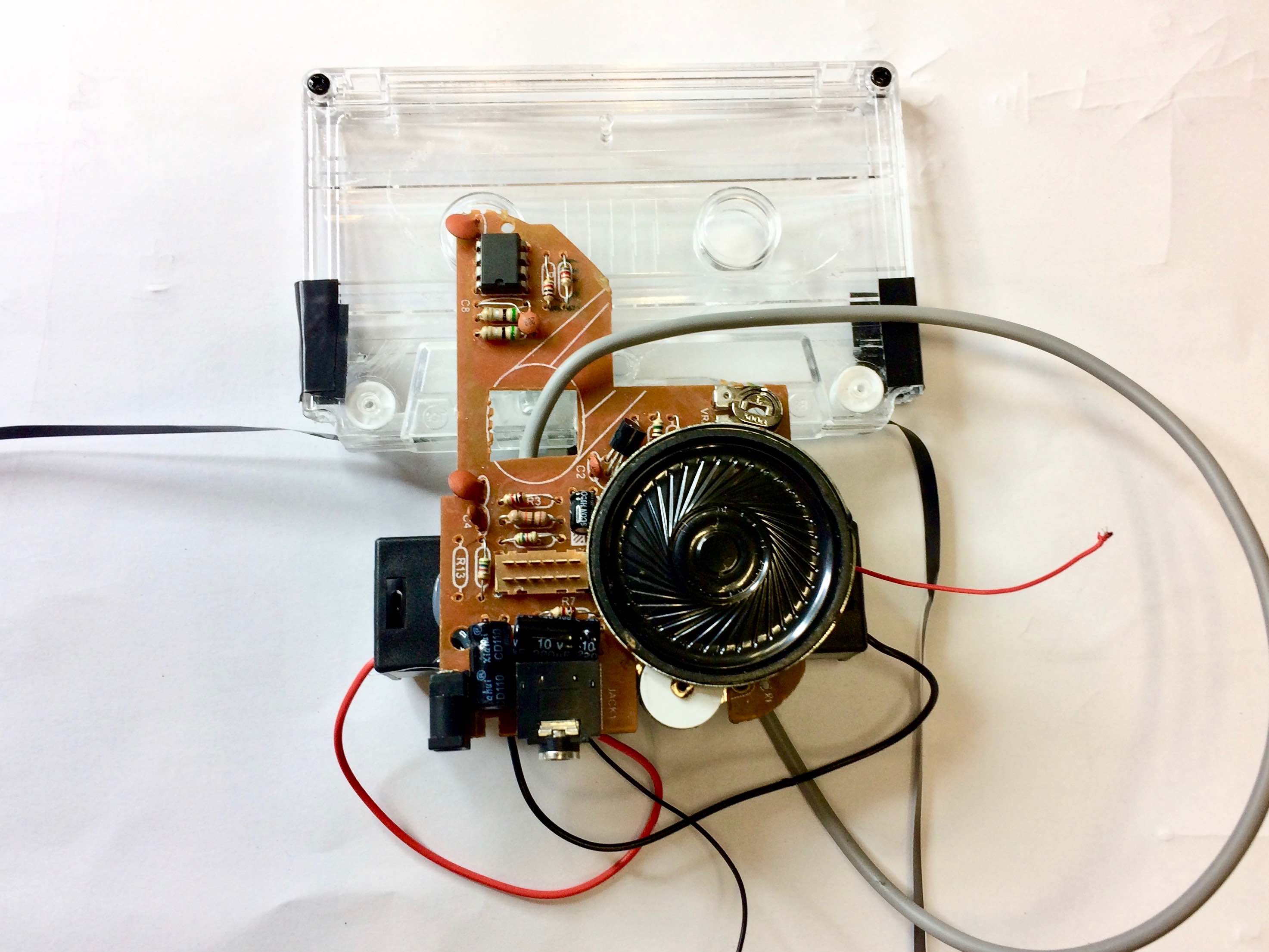

Pre listening tape making thinking

We’ve started by playing with tape and begun development on our tape based listener, a device that travels forward and back along a strand of magnetic tape alternately listening (recording to tape) and speaking (playing back from tape). To listen or speak it must move. The raising and lowering of one end of the tape is used to accomplish this. We envisage a rake of these listeners installed in a room. This is some form of surveillance. But out in the open. A congregation of daft machines that feel obliged to record your utterings, and their own, and then warble them back, sometimes in reverse. Comical machine listening implemented by a real stupidity. A flock of mad listening blurting machines some of which try to hide away from humans. Running along their tape. Noting the sounds of each other and the humans in the rooms or singing out earlier secrets captured.

Moving speaking listening tapehead prototype #1

In this enquiry we aren’t moralising as to how we should talk nicely to machines. We are more interested in how playing with algorithmic listening might open up fertile avenues of exploration with regard to human relations.

To be continued…

Augustion Di Scipio (2002). Systems of embers, dust, and clouds: Observations after Xenakis and Brün. Computer Music Journal, 26(1), pp.22-32. ↩